I

The term “knowledge society” is an amorphous idea, meaning many things.

- A society where information and ideas are available in quantities and ease of access never seen before in the history of mankind.

- A society where the ‘mode of production’ is based on knowledge i.e., mankind’s modes of production have evolved from agricultural to manufacturing/ industry and now to knowledge.

- A society where Man’s relationship with knowledge is undergoing a change – from viewing knowledge as a resource for learning about the world, to viewing knowledge as an instrument for engaging with the world differently and finally as an end in itself.

In this paper, we focus on the third dimension of the knowledge society – Man’s evolving or transforming relationship with knowledge – as the foundation for the knowledge society we will see emerging in the 21st Century.

The knowledge society has, thus far, been characterized by six key trends.

- The growth in communication technologies such as internet, mobile, and satellite television. These technologies have enabled information to be transmitted cheaply and effectively to all parts of the planet.

- The growth in ‘enabling tools and models’ that allow individuals to exploit these possibilities in several ways. These take on the form of social networks like Facebook and Twitter, search mechanisms like Google – a space of continuous rapid innovation especially in the first decade of the 21st Century.

- The consequent explosion in knowledge co-creation in society, i.e., millions of users are creating content (comprising their own ideas, thoughts, and opinions), with instant distribution capacity – through their membership of social networking sites, blogs, and putting up their own content for the world to see. This knowledge co-creation is allowing the emergence of multiple new thought streams – lending legitimacy and a new global peer community, to political, social, and personal concerns of all kinds.

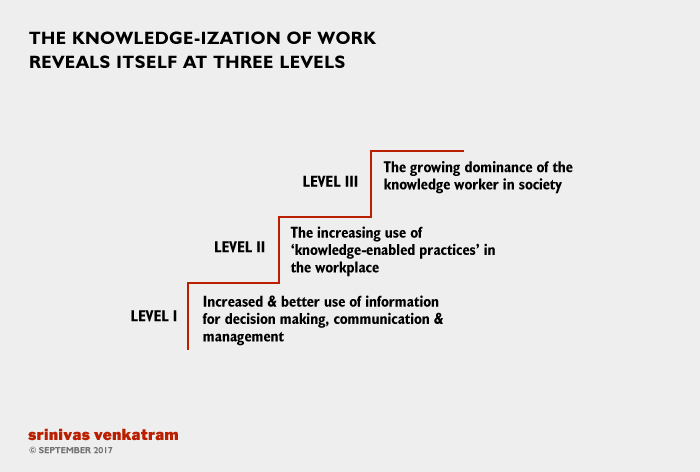

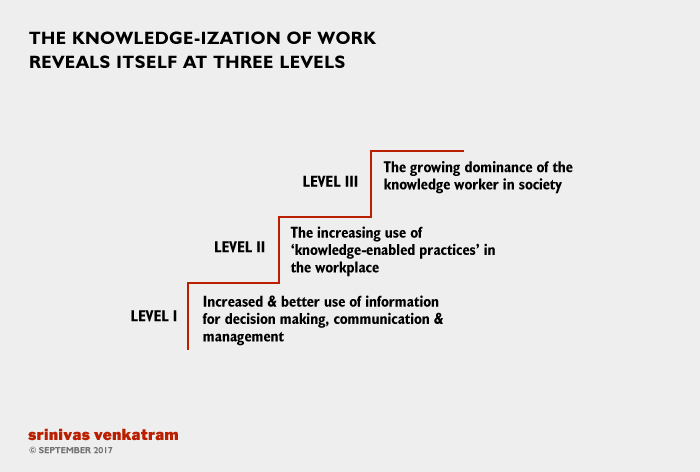

- The development of knowledge-based workplaces which has meant

(i) availability and use of better information for improved decision making

(ii) the need for almost everybody to become a knowledge worker of one kind or the other, (iii) the development of efficiency tools for management of enterprises, (iv) the development of knowledge enabled services such as customer support helplines both within and outside the organization.

- The transformation of value in traditional devices, by introducing automation, communication and ‘intelligence’ into these devices. This has resulted in enhanced responsiveness, connectivity and ‘value to user’ of these devices.

- The emergence of IT-enabled educational models such as (i) the availability of world-class content from top universities, (ii) the availability of content at low cost due to the use of digital formats, (iii) the possibility of new rich educational content, etc.

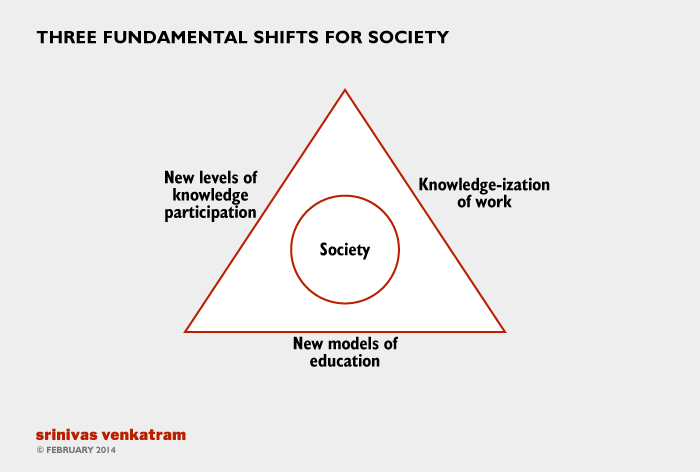

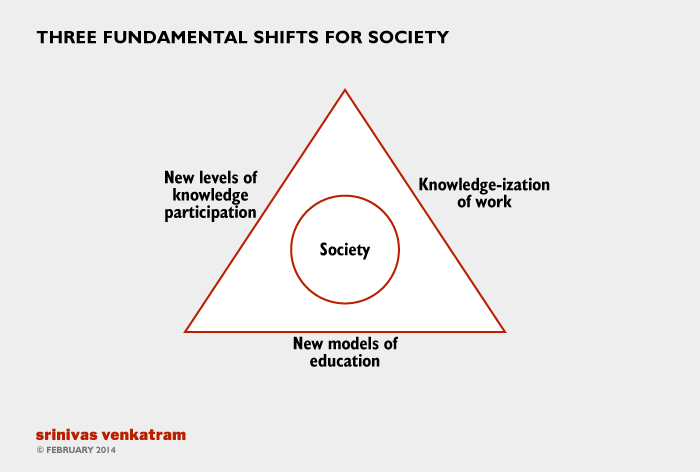

All these point to three fundamental shifts for society:

1. The knowledge-ization of work reveals itself at three levels:

2. The growth in ‘knowledge participation’ in society reveals itself as:

3. The evolution in educational models in society is revealing itself at three levels:

The Journey of the Knowledge Society thus far –

II

What we have described thus far is the “access revolution” – access to information and knowledge that gradually transforms: how people work, take decisions, and interact with each other, and so on. These shifts are themselves breathtaking in their scope and impact.

But there is a second, deeper, and more profound aspect of the knowledge revolution that is slowly unfolding in the world. This aspect refers not to the availability and use of information and ideas, but instead refers to how people are assimilating these ideas and thereby transforming their vision of life, their notions of purpose, meaning, fulfillment, and contribution.

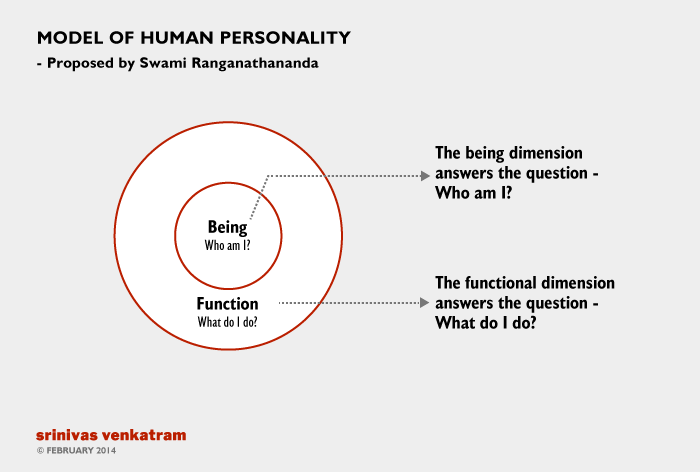

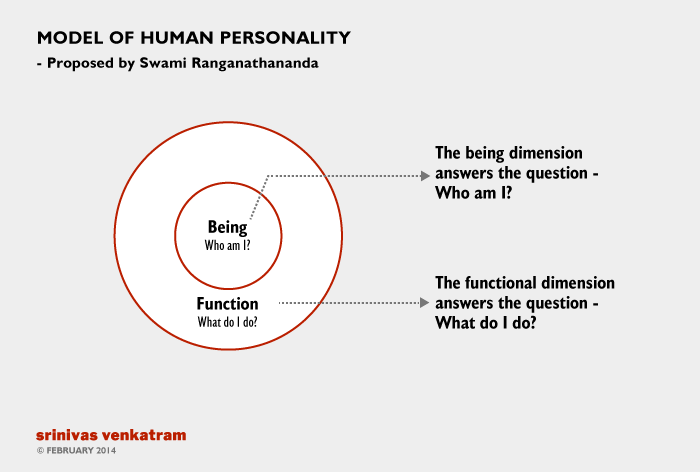

These two areas of evolution of the knowledge society will be better understood when we consider the following model, which Swami Ranganathananda proposed about 40 years back:

In the light of this model, we can classify knowledge into types – functional knowledge and being-level knowledge.

Knowledge when connected to the function dimension of the personality is perceived and interpreted in the context of an external or objective reality. It takes on the form of data, information, and analysis, and may be called functional knowledge.

Knowledge when connected with the being dimension of the personality takes on the form of individual vision, meaning, purpose, fulfillment. It can be called being-level knowledge.

These two types of knowledge – function-level knowledge and being-level knowledge have, in previous centuries, been distinct and unconnected. The West has been relentlessly focused on the access, comprehension, and use of functional knowledge, while the East has been largely focused on the inner transformation and development of being-level knowledge.

This is about to change.

III

As the knowledge society unfolds, we are beginning to see a new vision of knowledge – built around a harmonious integration between functional knowledge and being-level knowledge.

This harmonious integration is a product of assimilation of ideas. Indeed, Swami Vivekananda set the frame for this synthesis when he said that:

Education is not the amount of information that is put into your brain and runs riot there, undigested all your life. We must have life-building, man-making, character-making, assimilation of ideas. If you have assimilated five ideas and made them your life and character, you have more education than any man who has got by heart a whole library. If education is identical with information, the libraries are the greatest sages in the world, and encyclopedias are the Rishis.

It is this vision that has silently begun to unfold in society.

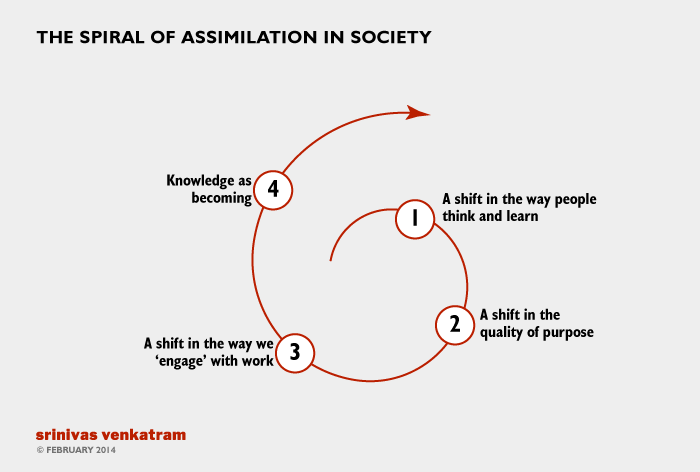

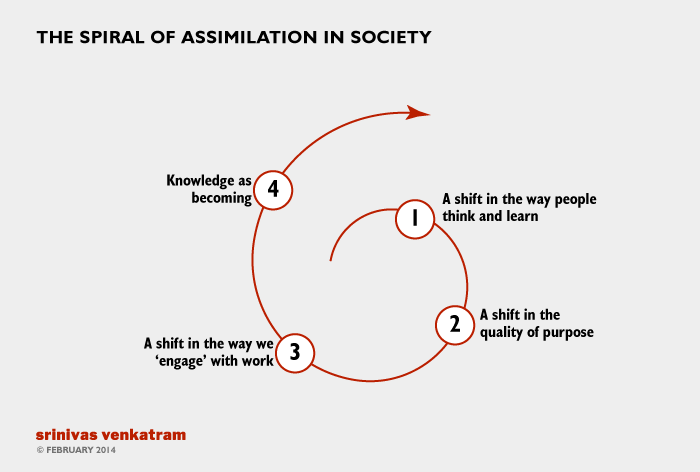

The first manifestation of this vision is a growing recognition that access to knowledge must be accompanied by three critical and concomitant changes:

(i) A shift in the way individuals think and learn

(ii) An appreciation of the purposes and goals to which this knowledge is applied

(iii) A shift in the Man’s engagement with work

A shift in the way people think and learn

For long it has been assumed that the only way to deal with information and knowledge is by collecting, collating, analyzing and deriving insights from knowledge. This has led to an empirical/ experimental view of knowledge deriving from the days of Francis Bacon and other Enlightenment Thinkers.

Organizations and individuals have now begun to recognize that unlimited access to knowledge does not necessarily help them think better, or find solutions to the challenges they face, or even more important, find meaning or purpose in whatever they do.

Thus, in the past few years, altogether new ways of thinking and working with knowledge have begun to emerge. These methods, currently classified as design thinking, solution thinking, etc., do not begin with functional knowledge (i.e., data & information), but instead with being-level knowledge – i.e., what purpose do I seek to accomplish in my life or what contribution I seek to make. The function-level knowledge that helps me organize, synthesize, and “construct” answers or approaches that serve my being-level requirements follow.

This shift in primacy from function-level knowledge to being-level knowledge is resulting in altogether new ways of dealing with available knowledge in the world.

A shift in “quality” of the purposes to which knowledge is applied

As individuals and organizations begin to take empirical and “function-level” knowledge for granted, and shift their focus to “being-level” knowledge, a second related shift has begun to take place.

Individuals and organizations have begun questioning the quality of purposes they seek. For example, Is the purpose of a corporation merely to maximize profits for shareholders or is it also to make a positive impact on the society and communities in which it operates? At an individual level, the question could be – What is the true purpose of my career – is it to achieve a high position in a corporation or is it to make a significant contribution to the world in and through my career?

This self-questioning and self-review of “quality of purpose” has led to ideas and movements such as conscious capitalism, higher ambition, shared value, good business, etc. all of which are leading to the development of citizen corporations or enlightened citizens who are concerned about expanding themselves beyond narrow self-interest to enlightened self-interest.

A shift in the way we do work

The search or seeking of a higher purpose for work has led also to a simultaneous need for a means to realize this desire.

Knowledge work is unique in this regard. Most forms of physical and industrial work, seek in society to create a division between the worker and the object of work. Knowledge work is unique in that it demands engagement from the knowledge worker. Put differently, a knowledge worker, in order to write a report or develop a solution to a problem must necessarily become engaged and involved in the work – and cannot (like auto factory workers) be largely disconnected or alienated from the work at hand. This “engagement” between the knowledge workers and knowledge work has a second deeper dimension – i.e. it is reflexive in nature. The quality and type of knowledge work impacts the thought process, emotions, and “state” of the knowledge worker and vice versa.

Furthermore the deeper the knowledge work, the more it develops the faculty of concentration (which Swami Vivekananda held as central to all forms of learning) and more it awakens the individual’s reflexive capacities.

Thus, knowledge work – well done – can deeply integrate learning & doing at the functional level and at the same time, can create the conditions for deeper orders of engagement both with oneself and the work at hand.

Redefining knowledge in society

These three aspects set the stage for a fourth, and perhaps more fundamental change that is in its embryonic stages in society – the shift in the meaning of knowledge itself in society.

A few decades ago, knowledge or knowing was associated with memory and knowledge of facts.

As facts and information have become commoditized in society, knowledge or knowing become more associated with the faculty of handling knowledge effectively (collecting, collating, organizing, analyzing, critical assessment, etc.)

But in recent years, it is being recognized that the functional capacity to handle knowledge does not in any way help us answer the being-level questions of purpose, meaning, fulfillment, etc. that are reshaping the way people think.

Thus, quality of the individual’s being seems to have a direct relationship to the quality of purpose of that individual, and his/ her willingness to leverage knowledge in the service of that purpose. In that, knowledge or knowing is slowly being recognized as related to “being and becoming” of an individual and not mastery of facts or even the knowledge processing faculty of the individuals.

All these ideas were, of course, well-known in the Eastern spiritual traditions , but are now entering the mainstream through the assimilation of knowledge and the development of the knowledge society.

Conclusion

These four trends together may be seen as the deeper “spiral of assimilation” that has begun to unfold in society – a spiral that will grow in strength and intensity, leading to a knowledge society that not only works with knowledge outside, but also with knowledge within.

This is the future direction in which knowledge society is likely to unfold.

(Originally written for the book ‘Swami Vivekananda’s Vision of Future Society’ under the title ‘Knowledge society – directions for the future’, published by the Institute of Culture, Kolkata, February 2014)