The purpose of Precision Knowledge Interventions

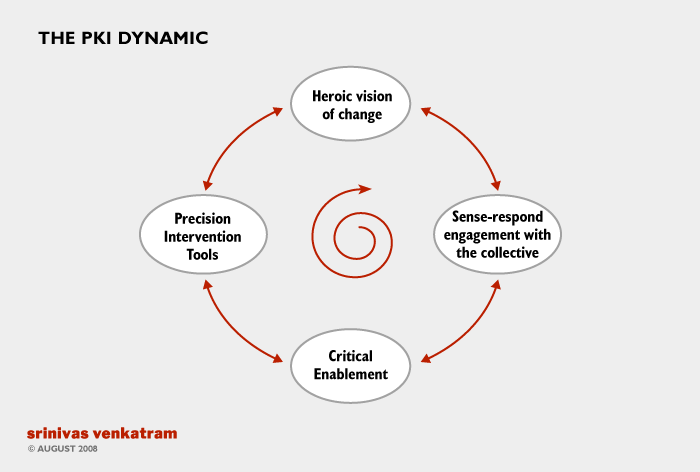

1.0 Precision Knowledge Interventions represent a model for engaging with change in a rigorous, scalable, and measurable manner.

2.0 The basic premise of the Precision Knowledge Intervention approach is that change must be clearly specified if we expect to succeed.

3.0 The word ‘specified’ is distinct and different from the word ‘envisioned’.

4.0 It is now well known that change must be envisioned with, and through, the collective undergoing change. It is also known that when individuals participate in and co-create the vision to be realized, then they are more likely to broadly support the initiative.

5.0 It is also well known that envisioning change and securing broad based buy-in into that change does not guarantee that the change will be sustained, and that people will indeed walk their talk.

6.0 This is where the word specification comes in. It is our experience, that there is an important stage in the change journey which is often ignored by practitioners. This is the stage when a “collective vision” is transmuted into “individualized seeing, within the context of the collective vision.”

This specification now becomes the basis of all enabling actions by the change leadership.

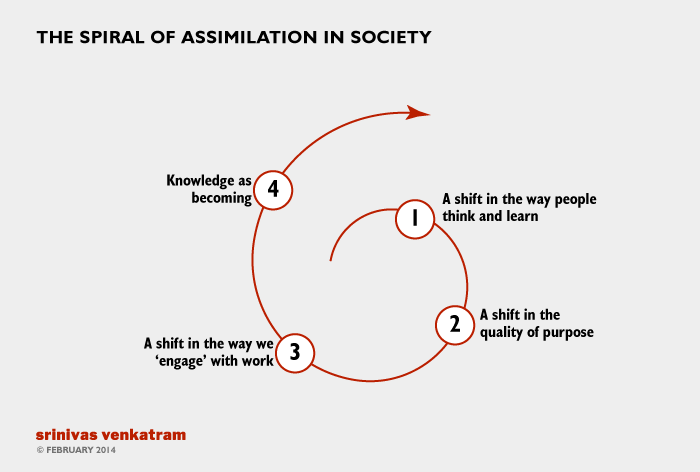

7.0 Put differently, it is assumed that people know how to translate vision into action. Nothing can be further from the truth. Most people are able to comprehend vision, but very few people are able to assimilate vision into their own lives.

8.0 To elaborate, every senior manager in a change-workshop may not only agree with, but also emotionally articulate the value and benefits of a proposed initiative. Yet, the Monday thereafter, when all the facilitators have gone back to their respective workplaces, the same senior manager faces the daunting task of changing the way he or she lives so that the new world is realized.

From Envisioning to realization

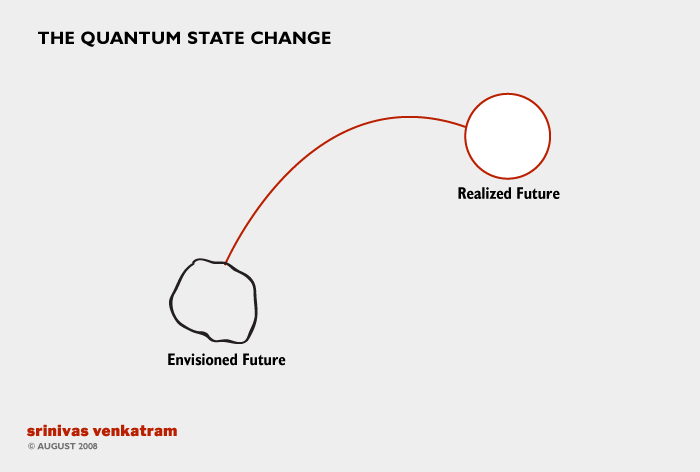

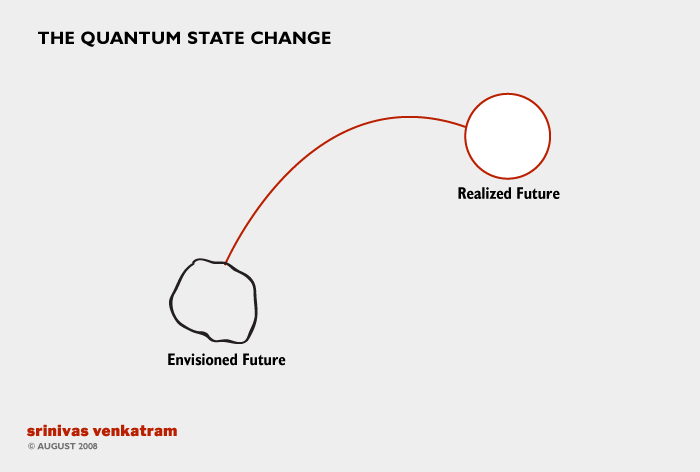

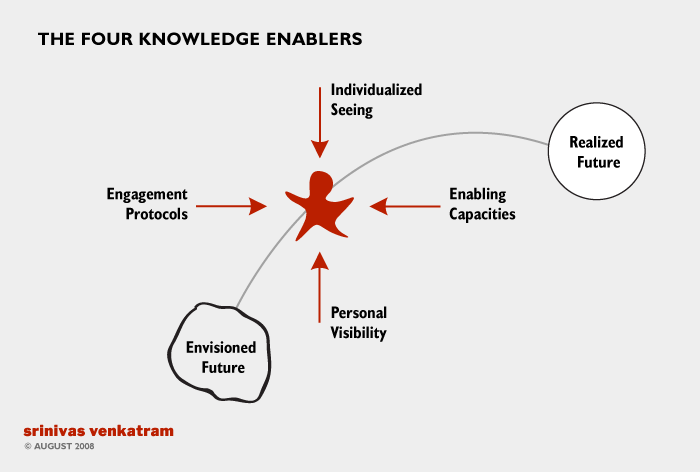

9.0 So what does the journey from an envisioned future to a realized future entail?

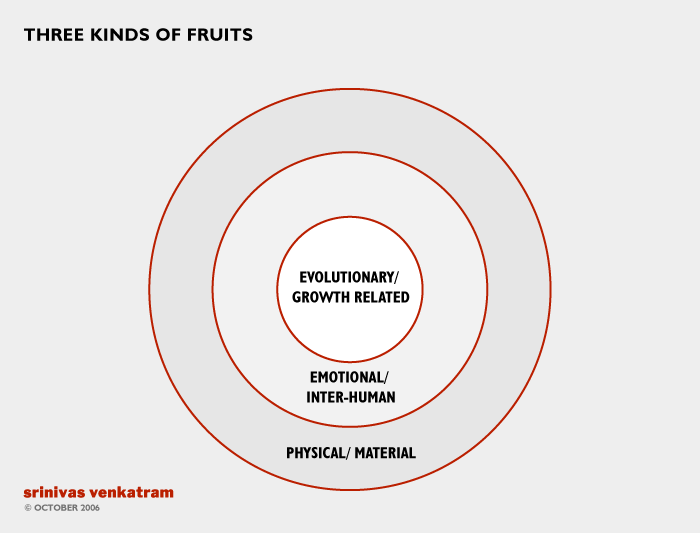

(i) The journey, first and foremost, involves a state change:

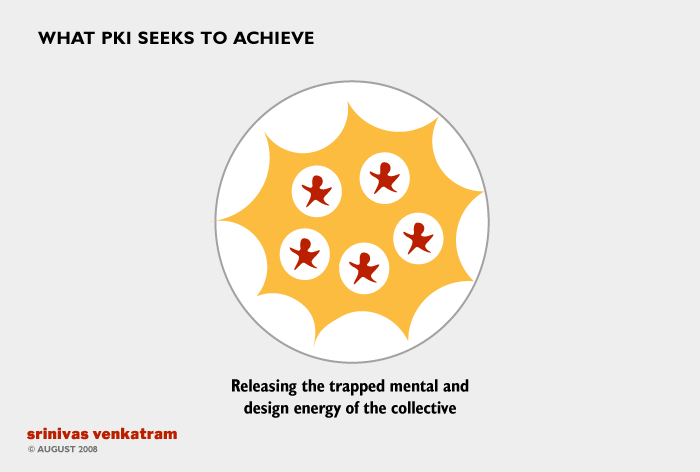

(ii) This state change requires a quantum leap in the collective. This quantum leap cannot be limited to the individual and extends to the collective which seeks to create a shared future.

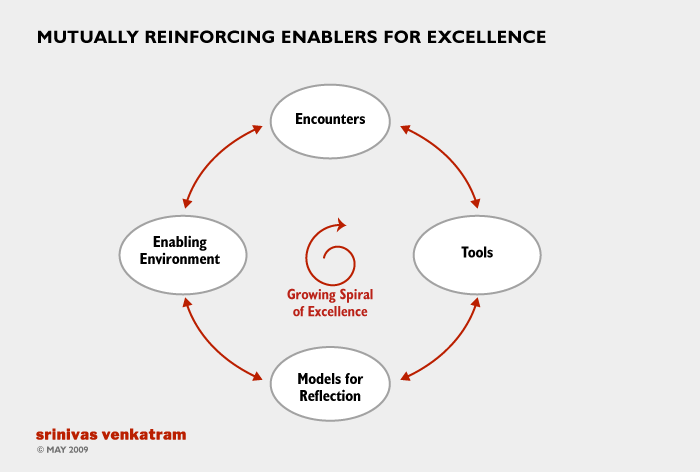

(iii) Further, the quantum leap in the collective requires that a set of diverse Knowledge Enablers need to be put into place simultaneously for change to be realized.

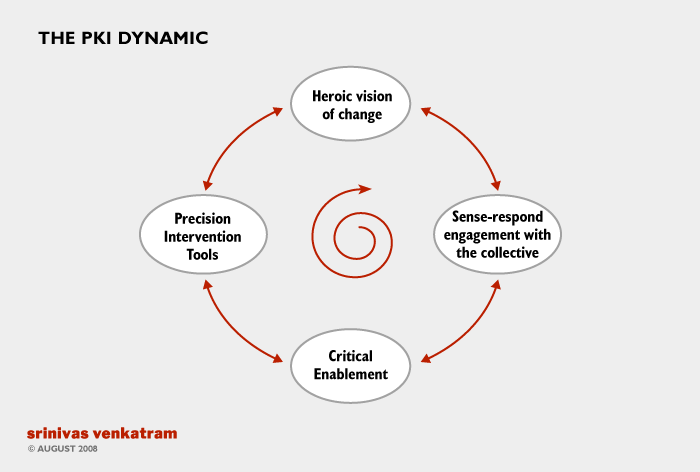

These two aspects of the change journey are explored in subsequent sections.

Mapping the quantum leap – Identifying key milestones on the journey

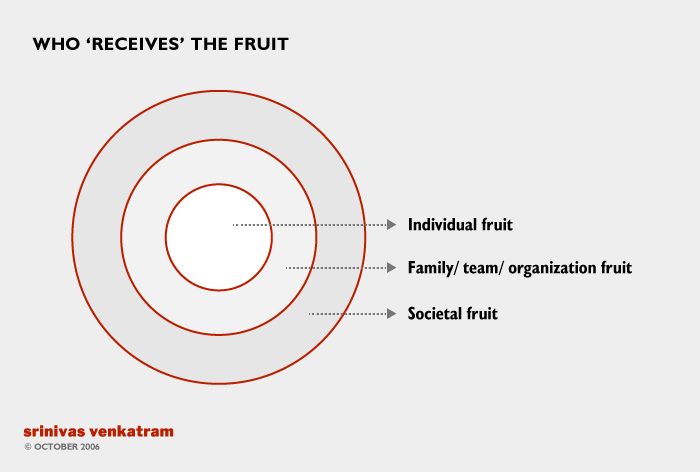

10.0 What is the nature of this journey from envisioned state to a realized state? The first insight is that there is not one but multiple change journeys taking place concurrently.

These change journeys take place at multiple levels:

(i) the journey of changing identity of key stakeholders as they encounter new roles, new purpose, new capacities and new contribution spaces.

(ii) the journey of external accomplishments as key design, operating, and business milestones are met.

(iii) the journey of transforming relationships, as key hierarchical, cultural, value, and power relationships are irrevocably reordered due to change.

(iv) the journey of increasing meaning and purpose, as the envisioned reality becomes progressively “real” or actualized in people’s lives.

11.0 It is hard to map these journeys and even harder to locate individuals at any one point in time on these journeys.

12.0 It is therefore a futile exercise to control or monitor this change journey effectively – except to celebrate some key milestones and to take action when some things “appear” to be badly going wrong.

13.0 How then to bring rigor to the mapping and modeling of this journey?

14.0 It is here that we introduce the notion of a “knowledge failure”.

We take the view that change is owned by the person making the journey, and the role of the change-leader is to provide critical enablements as the journey progresses.

A “knowledge failure” represents the absence of a critical enablement at the right time, to the right person, and in the right manner, in terms of re-specification.

15.0 This enables us to define the tasks of a Precision Knowledge InterventionTM. It has two functions; it

(i) scans for and diagnoses precisely ‘knowledge failures’ as these occur during the change journey, particularly at the level of the collective.

(ii) offers precision solutions that deal with these knowledge failures, on a sense-respond basis.

Defining the four knowledge enablers

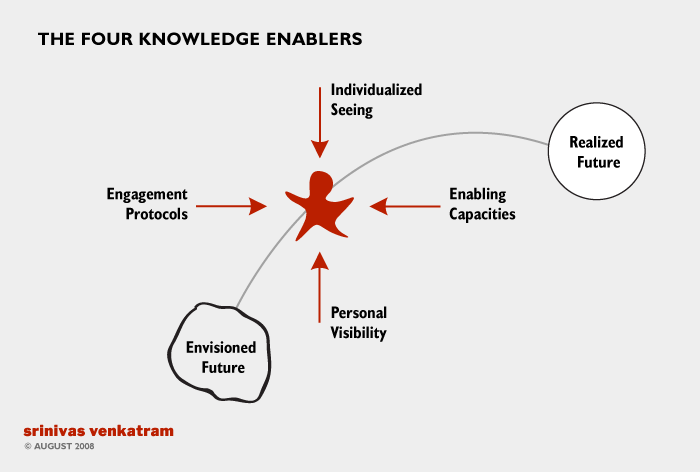

16.0 The four key knowledge enablers used in the Precision Knowledge InterventionTM approach are explored below:

17.0 If individuals in the system

17.0 If individuals in the system

– are not able to create their own individual visions,

– do not have the wherewithal to work upon the relevant enabling competencies,

– remain unsure of what contributions they are going to/ are expected to make,

– and don’t have institutional mechanisms to support their own integrity to vision,

then they are more likely than not, to fail in the change journey.

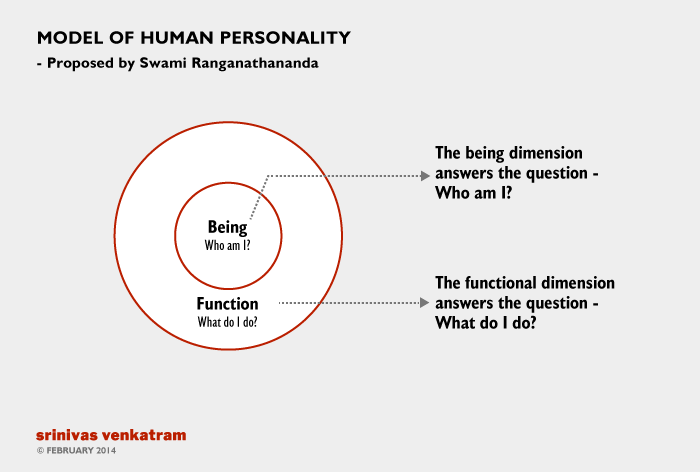

18.0 Individualized Seeing

Individualized Seeing implies that the envisioned reality must be seen not just in collective terms, but also in terms of each individual stakeholder in the system.

This translation from collective vision to individualized seeing is not a mere translation of the vision in terms of scale, but a wholesale re-specification of the vision from the language of institutional purpose to the language of personal meaning.

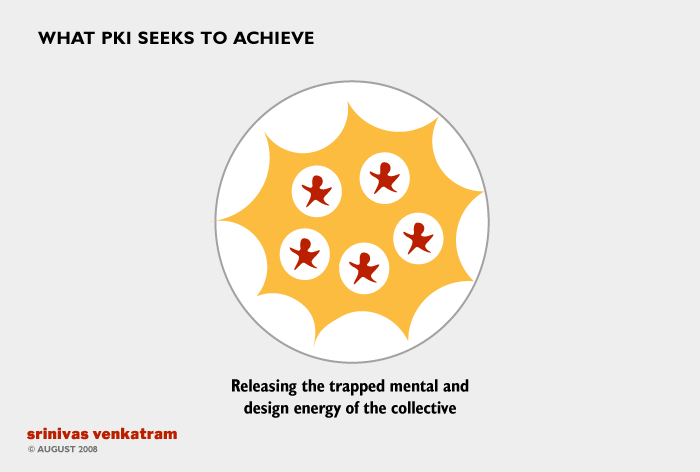

The power of individualized “seeing” is explicitated in the following diagram:

The Big Foot: Many individualized “seeings” in the context of one collective vision.

The Big Foot: Many individualized “seeings” in the context of one collective vision.

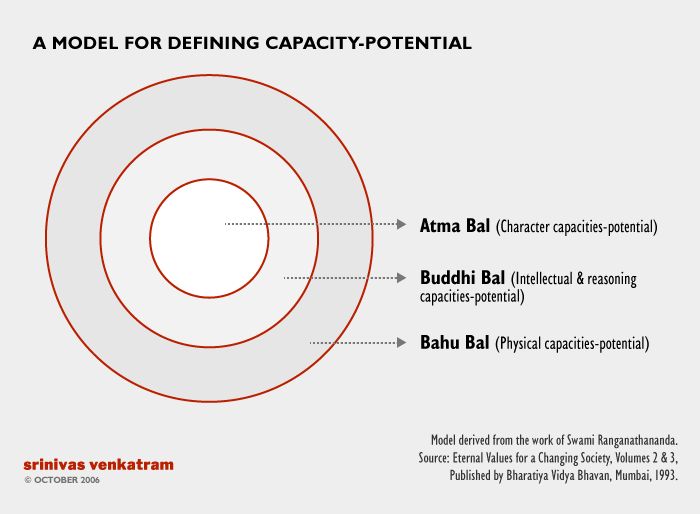

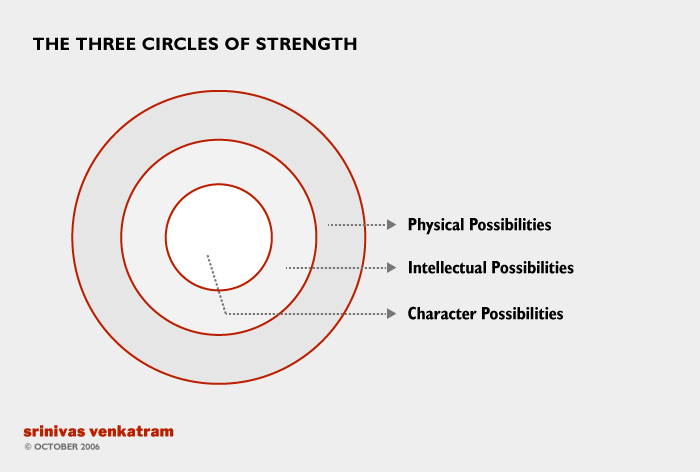

19.0 Enabling Capabilities

Almost always, change means a shift in relevant capacities – and reinterpretation (and re-specification) of what competence and professional practice means.

The important insight is that, in addition to new capacities being added, realizing change also means deep reinterpretation and reorientation of the core practices of the business itself.

In other words, deep, sustainable, change requires wholesale redesign of the very notion of expertise or competence within the business and reorienting individuals accordingly.

20.0 Personal Visibility

It stands to reason that any change in the business vision and concomitant change in one’s personal vision in the future, would threaten our carefully laid out plans for negotiating current organizational maps and relationship structures.

This aspect being closest to each individual in terms of what will happen tomorrow, it is obviously the most stressful and disabling dimension of change.

But for real change to succeed and sustain, every individual in the organization needs to find new spaces of contribution, value creation, and role-signaling in the envisioned future. This involves a fundamental re-specification of personal roles and visibility in the system.

21.0 Engagement Protocols

Engagement Protocols refer to the way people will work with each other in the future to be realized.

These protocols represent shifts in the organization’s operating culture – where do decisions get taken? how are the distances between functional silos to be negotiated? how do key people, product, developmental, and business lifecycles stay protected in a new environment?

It is easy to ask an organization to shift to teaming, responsiveness, collaboration, and empathy, or behave in this manner during the course of a change project. It is an altogether different thing to ensure that people walk this talk on a sustainable basis.

Engagement Protocols imply that a set of ideas such as teaming, responsiveness, collaboration, and trust need to be translated into “mechanisms” which will allow such behavior to flourish and be rewarded in course of time.

These mechanisms protect and enhance the quality of “group outputs” such as business decisions inter-functional relationships, protecting product and business life-cycles etc.

22.0 We have found that the absence of even one of these four Knowledge Enablers could result in an inability within the collective to complete the realization journey from envisioning to realization.

Designing successful Precision Knowledge Interventions

23.0 Designing successful Precision Knowledge Interventions implies

(i) being able to map out where critical enablement may be needed so that potential knowledge failures are anticipated to the extent feasible.

(ii) having an array of precision-transformation interventions and tools that are already tested, and proved, which can be deployed rapidly, and the real-time design capacity to develop new tools for new classes of knowledge failures

(iii) having a sense-respond engagement with the collective, so that potential knowledge failures are identified early, and potential solutions rolled out.

(iv) most important, rescripting change journeys as narratives of adventure and heroism, with the critical enablements being crucial “tools” and “weapons” in the journey to realization.

Diffusing Precision Knowledge Interventions: Some Criteria

24.0 Clearly the design of Precision Knowledge Interventions is complex:

(i) every one of these knowledge enablers must be “owned” by every individual in terms of day to day realities of the change journey. This means that traditional communication models that may actually hamper change, will have to be replaced by new models involving co-creation and co-emergence of knowledge in communities.

(ii) the Precision Knowledge Intervention encountered by one member of the collective, may be very different from another member of the collective. This implies that Precision Knowledge Interventions represent an array of change enablers that are delivered on a mass customization basis through a large scale business system.

(iii) a Precision Knowledge Intervention must be capable of being deeply contexted into the business, social, and technical practices of the change collective. This requires institutional arrangements to be created within the organization that will allow such deeply contexted Precision Knowledge Interventions to be developed and diffused.

The Value of Precision Knowledge Interventions

25.0 Precision Knowledge Interventions is a new social technology that enables businesses to significantly enhance the possibility of success in a change journey. They are effective because

(i) they enable individuals to dive deeper beyond vision, into the actual specifics of change,

(ii) they support individuals by “being available” rather than “driving change”,

(iii) they ensure that energy is released by a deep reframing of the socio-technical consciousness of individuals in workplaces.

Applying Precision Knowledge Interventions to solve integration challenges

26.0 Can Precision Knowledge Interventions be used to resolve significant integration challenges in large business and social systems?

27.0 The answer is affirmative, when the four key classes of knowledge failures are mapped and the need for the four knowledge enablers established.

(i) Individualized Seeing: The shared vision of a collective need not acknowledge individual aspirations of specific groups. This leads to a “hidden drag” on change as specific groups do not put their full weight behind a change journey.

The act of specifying individualized seeing in the context of collective change forces these differences into the open.

(ii) Enabling Capabilities: When diverse groups integrate (for example from different divisions, different countries, or different educational backgrounds), the critical concern is ensuring that diverse groups benchmark against consistent expectations of quality, execution, behavior, and operational tactics.

This class of knowledge failures needs intervening enablers in terms of appropriate capacities – not to achieve consistency of competence, but to ensure consistency of outcomes across groups.

(iii) Engagement Protocols: The value of engagement protocols in integration is self evident. Indeed, modes of interaction, unless formally mapped and reviewed, can make the daily task of working together stressful and disabling during the integration process.

(iv) Personal Visibility: Finding new contribution and role signaling spaces is one of the most difficult aspects of integration, especially in business settings where work practices often evolve in unique historical patterns.

Thus all four types of knowledge failures reveal themselves in the integration process.

28.0 Precision Knowledge Interventions has been fundamentally designed for enabling individuals in large collectives to realize the journey from vision to realization. However, the same approach could also be used to resolve related change challenges such as integration of diverse groups within a large collective.

(Paper originally presented at the Third SOL Global Forum on ‘Bridging the Gulf: Learning across Organizations, Sectors, and Cultures’ organized by the Society of Organizational Learning at Muscat, Oman in April 2008)

17.0 If individuals in the system

17.0 If individuals in the system The Big Foot: Many individualized “seeings” in the context of one collective vision.

The Big Foot: Many individualized “seeings” in the context of one collective vision.